Shared responsibility is also responsibility

Criteon Judgement – Amsterdam District Court⌗

In October 2023, the Amsterdam District Court ruled against the advertising service provider Criteon in an interim decision1 and ordered it to immediately comply with the deletion of tracking data requested by the plaintiff.

Importance 5/5

Powerfulness 2/5

Accuracy 4/5

Legal standards Art 26 GDPR

Data Privacy Pattern: Joint Controllership, Dataprivacy by Design

Legal standards: Art 25 Data protection by design and by default, Art 26 GDPR Joint controllership

Findings⌗

- Joint controllership under the GDPR does not mean limited responsibility

- Willingness to fulfill data subject rights does not cure a legal basis that was lacking from the outset

- Legal protection does not replace a lack of “privacy by default” and “privacy by design”2

Introduction⌗

In October 2023, the Amsterdam District Court ruled in an interim decision1 against the advertising service provider Criteon and ordered it to immediately comply with the deletion of tracking data requested by the plaintiff.

Facts of the case⌗

Criteon is an international advertising service provider. It provides its customers with software for integration on their websites for the targeted display of advertisements. The software is based on JavaScript and uses tracking cookies to uniquely identify website visitors and evaluate their behavior. The tracking cookies assign a UID with which users can be uniquely identified worldwide and recognized across websites.

Criteon receives the tracking data of all its customers who have activated the software via the software, processes it and compares it with other providers of advertising services.

Criteon contractually obliges its customers to obtain the consent of their website visits (as end customers) for this procedure, but does not check either technically or organizationally whether they actually comply with this obligation.

Criteon has presented its conduct in the proceedings with these arguments as fully compliant with data protection and legal requirements:

- since Criteon contractually obligates the website operators, it is their responsibility to obtain consent from (their) end customers.

- if someone objected to this or if the consent of an end customer was missing, Criteon would comply with its data protection information and legal obligations at all times.

- finally, users could prevent tracking at any time via the browser settings and an explicit opt-out.

The court did not follow this reasoning and ruled in favor of the plaintiff.

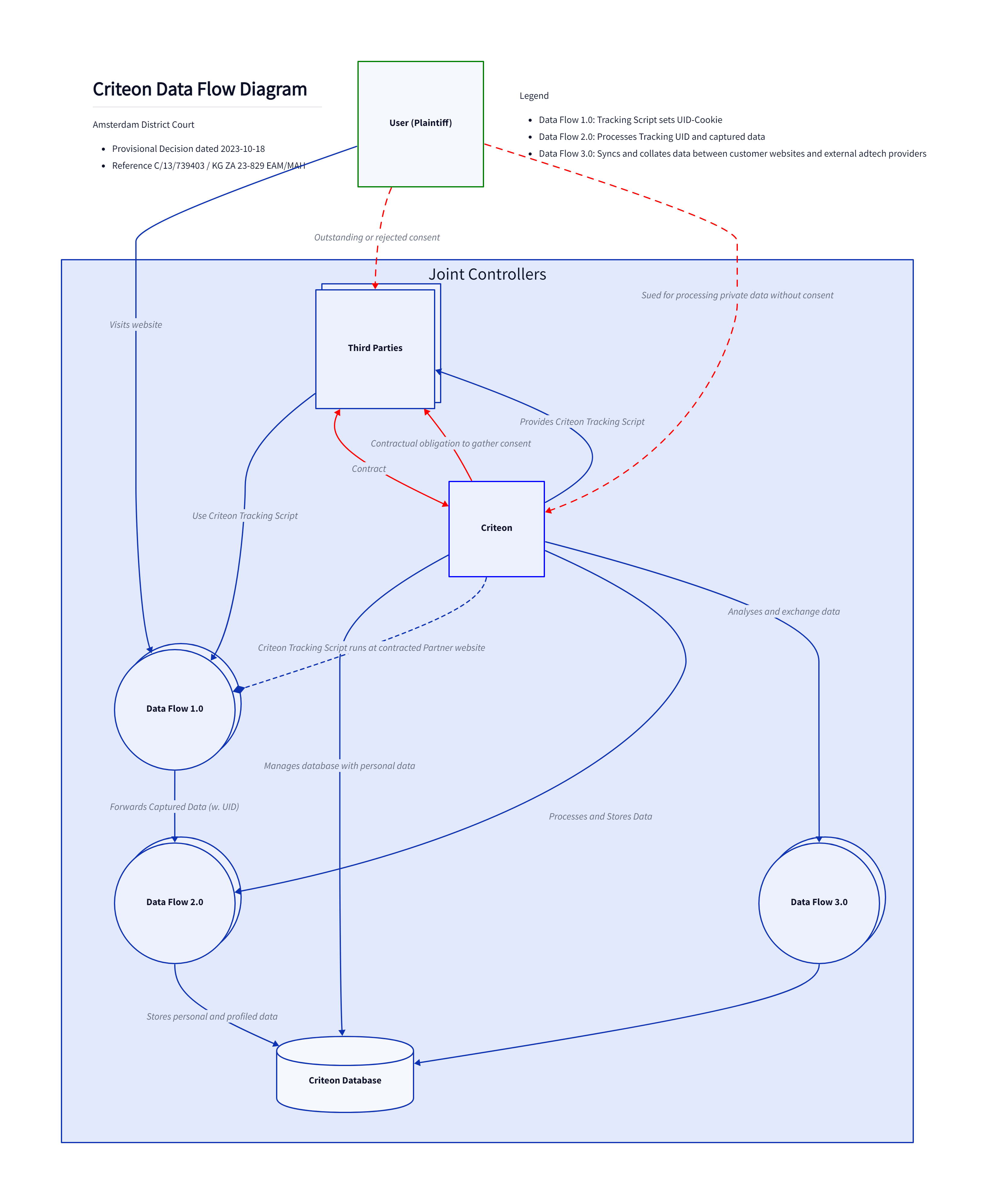

Data flow analysis - visual data privacy pattern⌗

We see three relevant data flows in the data flow diagram3:

- (1) the tracking of data on the website using the software provided by Criteon.

- (2) the forwarding of the data to Criteon using the same software and its processing, storage and aggregation with existing data by Criteon.

- (3) the forwarding or disclosure of the data and the comparison with other providers

We also see there that the lack of consent of the end user (visitor to the Criteon customer’s website) makes not only the first but also the other two data flows, which run under the sole responsibility of Criteon, illegal.

Legal assessment⌗

Shared responsibility: meaning and implications⌗

Responsibility for data processing lies with the person who decides on the purpose and means4.

Since the software originates from Criteon (means) and implements its business model (purpose), Criteon is certainly the controller(s).

The website operator is a customer of Criteon, installs its software on its website and receives remuneration for this. He also has an interest in this (purpose) and has chosen Criteon as the provider (means) and integrated its software on his website.

The ends and means are by no means symmetrically distributed: On the one hand, Criteon as an internationally active company that drives its business purpose through its own software and infrastructure; on the other hand, a large number of customers who merely operate a website and use Criteon’s service.

However, this uneven distribution does not prevent a clear classification as joint controllers in accordance with Art. 26 GDPR: Accordingly, each of the joint controllers should be approachable as a possible contact person for data subjects concerned and the data protection authorities and the conduct should be attributable to them.

This also means that both parties must each take all measures that are required for legally compliant data processing: Criteon may very well delegate the obligation to ensure user consent to the website operator, but is not relieved of the obligation to do so; in this case, it must regularly request and receive proof from the website operator that this is actually being done.

Nemo plus iuris transfere potest quam ipse habet⌗

In addition, the lack of consent for the initial setting of the tracking cookie in data flow 1 also makes the further data flows 2 and 3, which take place under the sole and direct responsibility of Criteon, unlawful.

The consent for the further data flows is not cured simply because Criteon had contractually outsourced the obligation to obtain the initial consent.

“Unlawfulness by default” is not a good argument⌗

Criteon also rightly failed with the argument that, if users do not like the service, they could opt out of their service or reject cookies altogether via the browser settings.

This would not cure the obvious fact that Criteon had previously implemented its business model unlawfully in relation to the GDPR, as it clearly violates a whole range of fundamental data protection principles: In addition to the transparency requirement, which requires disclosure of processing in advance, purpose limitation, the principle of data mining and that of unauthorized profiling.

Privacy by design and default⌗

Since Criteon has set up and marketed the entire service with all data flows worldwide, it is also difficult to understand why obtaining consent is missing as a core function in this software package, which in turn contradicts the principles of privacy by design and privacy by default.

The preliminary injunction is therefore correct on several legal grounds and it is to be hoped that it will be upheld in the next instance.

Risk analysis⌗

Finally, let’s carry out a risk analysis in the form of a data protection impact assessment.

We will apply the Solove5 taxonomy, which distinguishes the risks with regard to the collection, processing, manipulation and distribution of data.

| Aspect | Assessment | Risk (1-5) |

|---|---|---|

| Collection | Criteon collects clearly assignable user data from countless websites worldwide without providing a legal basis | 5 |

| Processing | Criteon processes and stores this data persistently in large databases without a secure legal basis | 5 |

| Invasion | Criteon analyzes this data and links it to create predictions about suitable advertisements (profiling) | 5 |

| Dissemination | Criteon distributes the data and compares it with other providers. | 5 |

The unsecured legal basis of the initial data collection means that all further data flows are also potentially unlawful. This creates an enormously high risk in every aspect of data privacy protection, the potential impact of which (ImpacT) is exacerbated by Criteon’s international orientation.

Summary⌗

Criteon’s objection that they cannot obtain the consent of every end user is unfounded and pretextual. Their counter-argument that a more restrictive approach would jeopardize their business basis is correct, because their business basis is obviously and at first glance unlawful and it is the idea of every legal system to prevent prohibited and sanctioned behavior.

What is astonishing about this ruling is that Criteon was able to expand so much with this concept in the first place and that it was only many years after the GDPR was enacted that a Dutch district court, of all places, issued a temporary injunction prohibiting it.

The fact that the GDPR suffers from a lack of coordinated implementation across Europe is once again evident here.

We will see to what extent the measures announced by the EU for a more effective and uniform implementation across Europe will take effect, especially with regard to large and internationally active companies6.

Appendix: Data flow diagram⌗

-

Amsterdam District Court, judgment in summary proceedings of 18/10/2023 - C/13/739403 / KG ZA 23-829 EAM/MAH Full text (NL): https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/#!/details?id=ECLI:NL:RBAMS:2023:6530 ↩︎ ↩︎

-

Guideline of the European Data Protection Board 4/2019 on Article 25 Data protection by design and by default privacy by design and by default, version 2.0, Adopted on October 20, 2020 EDPB, https://edpb.europa.eu/system/files/2021-04/edpb_guidelines_201904_dataprotection_by_design_and_by_default_v2.0_de.pdf ↩︎

-

Data Flow Diagram

↩︎

↩︎ -

Rosenthal, David: Controller or Processor: The Gretchenfrage under data protection law, in: Jusletter June 17, 2019 ↩︎

-

Solove, Daniel J.: Understanding Privacy, Harvard University Press, 2009 ↩︎

-

Krempl, Stefan: GDPR amendments should solve core problem of data protection enforcement, retrieved on 21.02.2023 ↩︎